In a world so relentlessly defined by utilitarian reasoning, by expedient thinking, by prose language, and by vicious speech, poetry is decisively out of place. Displacement, though, is what accounts for poetry’s extraordinary capacity for meaning. Relieved of the duties of routine language, released from the onerous burden of serving as a utilitarian vehicle of communication, poetry is free to soar and rove, revealing sublime sights (sights of tremendous beauty, sights of great terror) seldom, if ever, accessible to prosaic language.

In the Americas––in Latinx, Latin American, and African-American literature and art––there exists a practice of subverting picturesque notions of landscape in favor of more nuanced, historically-informed, politically incisive renditions of the natural environment. Poets have been at the forefront of this politicized understanding of landscape, re-inscribing it in ways that make apparent the traces of conflict and the traces of violence so often erased from the more idealized, more pastoral renditions of nature. Few poets have grappled with this notion of the environment with the force and the beauty that Raúl Zurita and Amy Sara Carroll breathe into their respective poetries of landscape.

A historically layered notion of landscape is evident in Zurita’s very first works: epigrammatic and somberly visual poems printed on plaster slates resembling tombstones. These and other poems by Zurita (his writings on the Atacama desert, on the New York skies, on the sea cliffs of the north Chilean coast) use beautifully terse language to give voice to landscapes of pain and political violence. In El hambre de mi corazón, an exhibition of Zurita’s landscape poetry at the David Rockefeller Center at Harvard University, these poems appeared prominently. They made visible the pains of our present, but through the historical lens of past abuses. They helped us remember distant violence by facing the deaths that take place at home, along the border dividing the United States from Mexico.

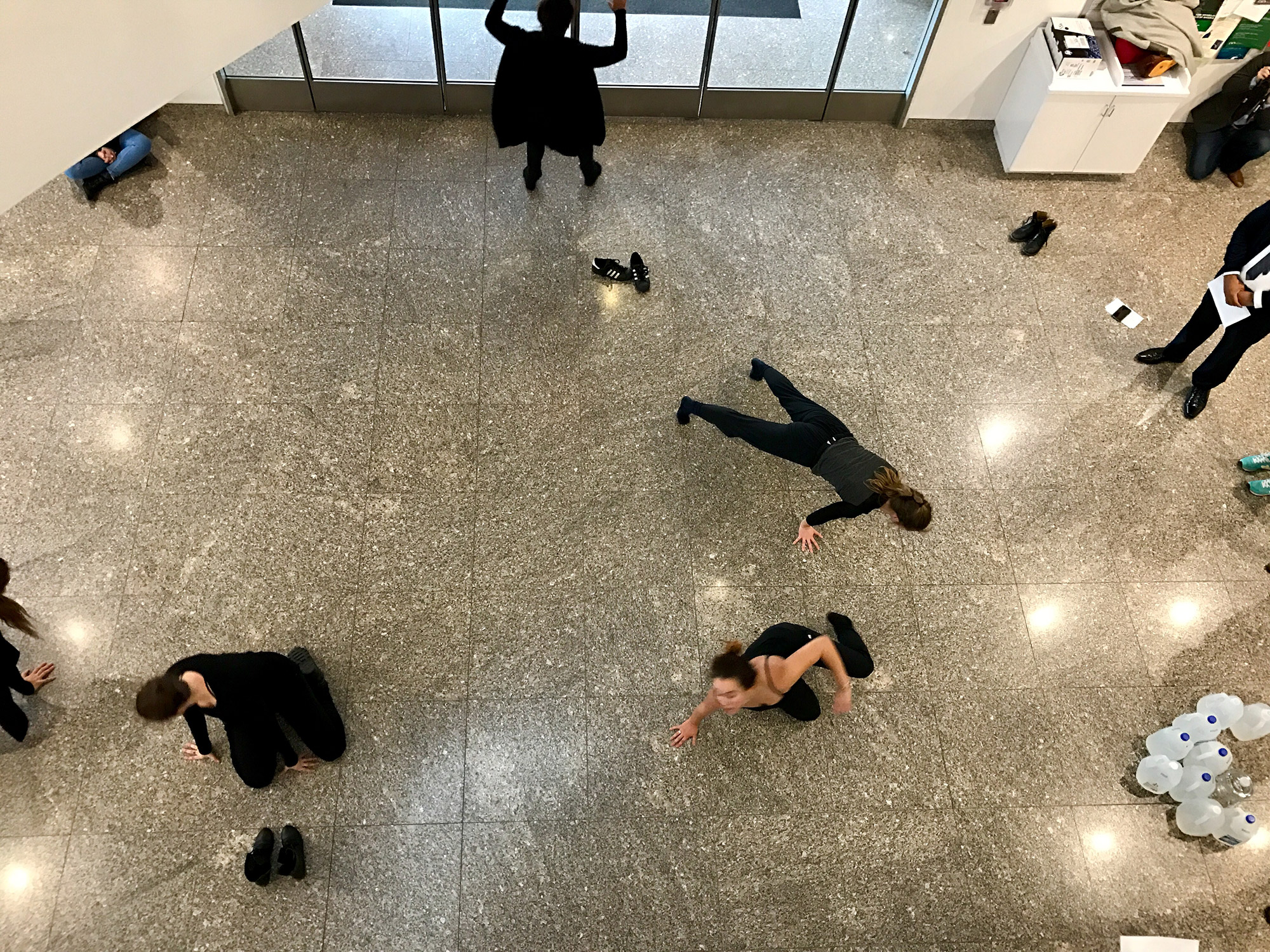

On Thursday, October 27, 2016, in the atrium where his poems are installed, Zurita read his Canto a su amor desaparecido to an audience of students, faculty, staff, and members of the community. In tandem with Zurita, a group of faculty and students read from Amy Sara Carroll’s “Desert Survival Series.” Like Zurita’s poetry, Carroll’s poems, though defiant in their embrace of the pragmatic and the prosaic, seek to intervene in and re-inscribe a landscape, a desert––the desert straddling the US-Mexico border. These poems are a central part of the [({ })] Transborder Immigrant Tool, a design project conceived of around the idea of distributing inexpensive, GPS-enabled cell phones to migrants planning to walk across the desert between the United States and Mexico. As mapped by Carroll’s “Desert Survival Series” poems, the Sonoran desert is restaged, or rather, re-screened. The desert gains visibility, though not as an entryway for furtive migrants. It emerges, rather, as a site deprived of sustenance, a place of ghastly loss, the final trek of so many undocumented migrants whose deaths now number in the thousands.

On a Thursday, on a campus on the Eastern Seaboard, we read Carroll’s desert poems and listened to Zurita reading his Canto. The double reading revealed for us, if only for a moment, the desert in particular and landscapes in general in all their terrible contradiction: as sites of magnificent beauty and scenes of (in)visible pain, places of unspeakable violence. For a moment, those of us present felt moved and strengthened, bolstered enough to witness together as one and the same thing all the beauty and all the pain of the environments that surround us. For a moment, it felt as if we had the power to resist the erasure of pain and violence that sustains a necessary illusion: the dream that we live in a land of “liberty and justice for all.” It was a moment to be cherished, especially here, especially now, in times when the work of remembrance, when the work of resisting what Carroll calls, citing Eve Sedgwick, the “privilege of unknowing,” is most called for.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Privilege of Unknowing: Diderot’s The Nun.” In Tendencies. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.